Coffee and coal

Slime Mold Time Mold published an interesting article titled “Higher than the Shoulders of Giants; Or, a Scientist’s History of Drugs”. I recommend reading it in full, but in case you don’t have the time, here is my summary.

I

Things are not as they used to be. In the last couple of years, the world has seen a reduction in economic and scientific growth that is sometimes called “The great stagnation”. Since the start of the enlightenment things had gone better and better. Growth had accelerated constantly, scientists had invented more awesome things and everybody got a little bit richer every year. Then, something happened. You can find a lot of graphs to support this claim at https://wtfhappenedin1971.com. The gist of it is, that in the early 1970s the American economic system started falling apart and could no longer deliver the rich harvest that its people had enjoyed for so long. Wages became uncoupled from productivity growth. Inflation started rising and never stopped. The US began taking on unprecedented amounts of debt. What had happened? There are a number of different explanations. Some blame the oil embargo, others the end of the gold standard. Slime Mold Time Mold blames the 1970 Controlled Substances Act.

In 1973 President Nixon, citing drugs as the cause for an increase in street crime, created the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which centralized the responsibility of cracking down on trade and consumption.

The authors try to make a case that this single event was responsible for The Great Stagnation by going through the history of mind-altering substances and their relationship to scientific progress. They start with coffee. Coffea beans didn’t reach Europe until the end of the Middle Ages and by the 18th century had established themselves across the continent. The British, especially, loved it.

The first coffeehouse in London opened in 1652 in St. Michael’s Alley in Cornhill, operated by a Greek or Armenian (“a Ragusan youth”) man named Pasqua Rosée. The coffee house seems to have been named after Roseé as well, and used him as its logo — one friend who wrote him a poem addressed the verses, “To Pasqua Rosée, at the Sign of his own Head and half his Body in St. Michael’s Alley, next the first Coffee-Tent in London.”

The Royal Society, the oldest national scientific institution in the world, was founded in London on 28 November 1660. The founding took place at the original site of Gresham College, which as far as we can tell from Google Maps, was a mere three blocks from Rosée’s coffeehouse. Some accounts say that their preferred coffeehouse was in Devereux Court, though, which is strange as that is quite a bit further away. But this may be because Rosée’s coffeehouse was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

In 1661, Robert Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist, which argues that matter is made up of tiny corpuscules, providing the foundations of modern chemistry. In 1665, Robert Hooke published Micrographia, full of spectacularly detailed illustrations of insects and plants as viewed through a microscope, which was the first scientific best-seller and invented the biological term cell. By 1675, there were more than 3,000 coffeehouses in England. In 1687, Newton published his Principia_._

Slime Mold Time Mold then goes on to make the same point about Cocaine and LSD.

While I am unconvinced of the general thesis and don’t think they gave the dangers of illegal drugs enough space, the point about coffee was new to me. I have maybe drunk it three times in my life, mainly because I am skeptical of free lunches and don’t want to become addicted. However, if what the writers write about the cognitive benefits, is true, that could be a game changer. If Paul Erdös couldn’t get stuff done without it, how could I?

II

There are several different theories on how coffee could be connected to increased productivity. One is simply that it served as a substitute for beer and prevented Europeans from being drunk all the time. From Malcolm Gladwell’s 2001 essay Java Man [1]

Until the eighteenth century, it must be remembered, many Westerners drank beer almost continuously, even beginning their day with something called “beer soup.” […]

Now, they began each day with a strong cup of coffee. One way to explain the industrial revolution is as the inevitable consequence of a world where people suddenly preferred being jittery to being drunk.

Others, such as this Huffington Post article [2] mention the rich possibilities for social and intellectual connections that coffee houses offered. In a time where the social order was largely predetermined by ancestry, coffee houses enabled men from different circles to freely exchange ideas and catch the latest news. Because I am not drunk all the time and have access to the internet, neither of these explanations would help me more productive through coffee. Thus, I will now explore the research that ties caffeine to cognitive performance.

Caffeine (birth name Guaranine Methyltheobromine 1,3,7-Trimethylxanthine Theine) is a stimulant that primarily works by blocking adenosine, an organic compound that accumulates over the day in the central nervous system and makes you tired. Even though it can be found in a number of different plants, we are mostly utilizing it in form of beans from the Coffea plant. The beans are then ground and intermixed with water to produce coffee. It is the most widely used psychoactive substance in the world [3].

This Review Article [4] summarizes years of research on the effect of caffeine on numerous components of cognition. The results are mixed. It claims that caffeine does not consistently improve active learning or short-term memory. However, the drug does produce positive effects if the subjects are sleep deprived or after lunch. The article also hints that caffeine might improve reaction time and can help sustain attention during difficult tasks. It concludes that caffeine is not a pure cognitive enhancer but has indirect effects.

Looking deeper into this, I found this double-blind placebo-controlled trial, which gave habitual consumers and habitual non-consumers either a drink containing either a placebo, 75 mg or 150 mg of caffeine [5]. The participants were required to abstain from caffeine consumption overnight, which was confirmed by testing salivary samples. The goal of the study was to determine whether effects are produced by the drug itself or the alleviation of withdrawal. A series of tests were used to assess the cognitive performance at baseline and after, of which I will present some of the ones with significant treatment effects. Please keep in mind, that I have no training in statistics, so I might be making some rookie mistakes here.

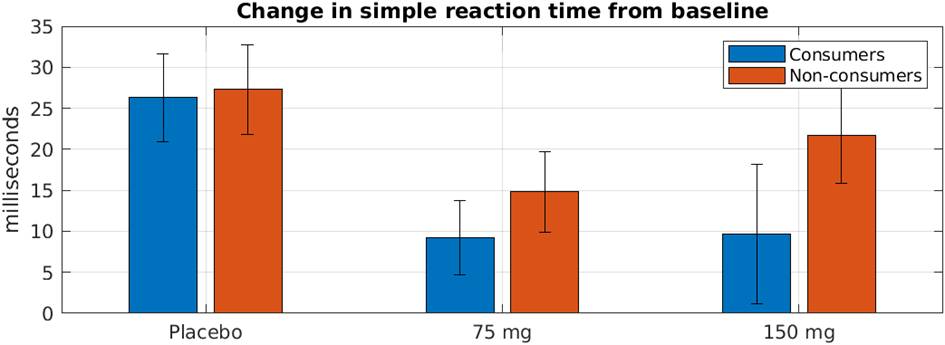

The first graph shows changes in reaction time from baseline half an hour after consumption. Reaction time was measured by requiring the participants to press a button every time the word “YES” showed up on a screen. You can find more details on the specific tests performed in [6]. The average baseline values for all six groups were between 279 and 288 ms and did not differ significantly here or on any other measure. If I interpret the data correctly, all groups got worse during the second test, but the consumer’s scores deteriorated less.

Only the differences between and the placebo and the 75 mg group are significant, however, there the stuff seems to work better for consumers than non-consumers.

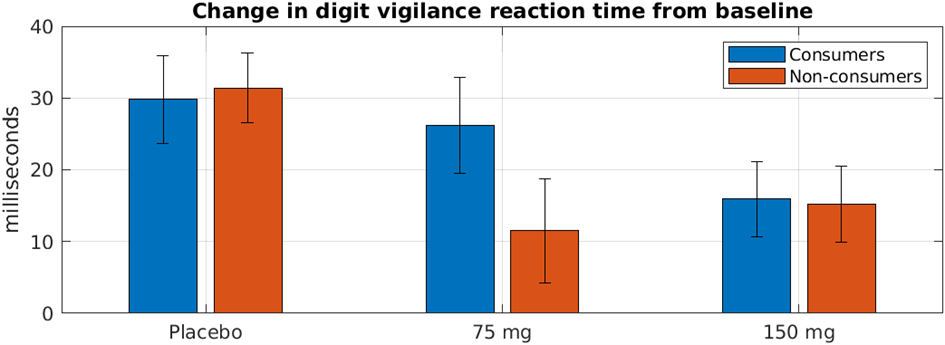

The second graph shows the result of a modified version of this test. Participants were presented with a series of digits and only had to react, if the digit shown matched a target. Here the difference between placebo and both of the treatment groups is significant, but now non-consumers seem to do a little bit better. I don’t have any explanation for this except that this study only used data from 30 participants.

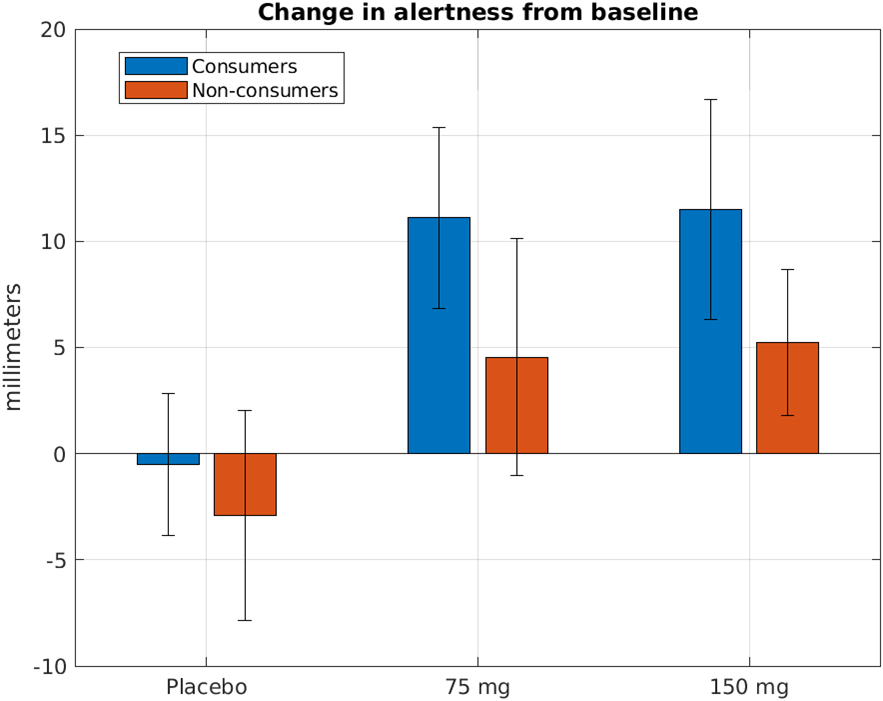

The authors also wanted to know how caffeine affected subjective scores of performance. The participants had to evaluate how alert and tired they felt on 100mm scales and a composite “alertness” score was calculated from it. That consumers show greater improvements than non-consumers makes sense, as the former are in withdrawal. That the effect on non-consumers is significant, is remarkable and a quite good sign.

III

I was a bit surprised by the outcome of my research. Caffeine as a cognitive enhancer seems to work only modestly and chiefly causes improvements in people who are sleep deprived or otherwise impaired. This strongly contrasts with descriptions I have gotten from friends as well as some internet surveys. This one asked hundreds of people to rate the effectiveness of various substances from zero to ten, where zero means “zero or bad on net” and ten means “life-changingly good”. 802 people had used caffeine and rated it a bit below 6.4 on average. It was the second most effective nootropic in the survey below modafinil, a medication used to treat narcolepsy-induced sleepiness. I also found this attempt to weigh the benefits of caffeine by a person named Gwern:

Finally, it’s not clear that caffeine results in performance gains after long-term use; […]. A cross-section of thousands of participants in the Cambridge brain-training study found “caffeine intake showed negligible effect sizes for mean and component scores” (participants were not told to use caffeine, but the training was recreational & difficult, so one expects some difference).

This research is in contrast to the other substances I like, such as piracetam or fish oil. I knew about withdrawal of course, but it was not so bad when I was drinking only tea. And the side-effects like jitteriness are worse on caffeine without tea; I chalk this up to the lack of theanine. (My later experiences with theanine seems to confirm this.) These negative effects mean that caffeine doesn’t satisfy the strictest definition of ‘nootropic’ (having no negative effects), but is merely a ‘cognitive enhancer’ (with both benefits & costs). One might wonder why I use caffeine anyway if I am so concerned with mental ability.

My answer is that this is not a lot of research or very good research (not nearly as good as the research on nicotine, eg.), and assuming it’s true, I don’t value long-term memory that much because LTM is something that is easily assisted or replaced (personal archives, and spaced repetition). For me, my problems tend to be more about akrasia [lack of will] and energy and not getting things done, so even if a stimulant comes with a little cost to long-term memory, it’s still useful for me. I’m going continue to use the caffeine. It’s not so bad in conjunction with tea, is very cheap, and I’m already addicted, so why not? Caffeine is extremely cheap, addictive, has minimal effects on health (and may be beneficial, from the various epidemiological associations with tea/coffee/chocolate & longevity), and costs extra to remove from drinks popular regardless of their caffeine content (coffee and tea again). What would be the point of carefully investigating it?

I think the author is right, that there are not a lot of downsides and caffeine might help with focus. One of my goals in life is to be bolder and try more new things, so I will coffee a try.

IV

So now that I have decided to get a taste of the stuff, how do I utilize it optimally? Continuous consumption will most likely result in addiction, which I want to avoid. Gwern already mentioned some of the negative effects stemming from dependence, but here is a first-person account:

I could feel myself getting sick on the last day. Just get through it, I thought. Sick later. Work today.

I got home, exhausted. The next morning I felt sick, wiped out, achy. There you go, I said. I have the flu. I struggled through work, taking naps when I could.

As the day progressed, I got worse. Weakness, tiredness, horrible nausea, headache. I gagged at the thought of food, but I forced myself to at least drink Gatorade. Gatorade is the artificially sweetened sweat of male bicyclists. Every word of that description disgusts me. I drank the purple one.

Day 2 came, and I was worse, not better. Not even the same– much worse. The headache was ruthless. The nausea had become motion sickness– turning my head was a lunar launch. The arthralgias, bizarrely, had disappeared– except in my neck, which had become very painful and stiff. I couldn’t turn my head well. I could barely walk, I could barely think.

I went to work.

The weakness and lethargy had also changed– into narcolepsy. It wasn’t weakness– I was drugged. I fell asleep for only a second at a time, but it overtook me every moment I wasn’t active. Driving. Watching TV. Standing at a urinal. On an elevator. During phone calls. I could not stay awake. Simply closing my eyes would drop me into Stage IV sleep. I could still be talking, but if my eyes were closed I was asleep. And what I said was nonsensical.

I was almost helpless. I took Tylenol. Motrin. Tylenol + Motrin. Nothing. And I could not stay awake. The head and neck hurt so much that the only solace was sleep, which I couldn’t stop anyway.

What kind of flu was this? And something worried me: why didn’t I have a fever?

By day 3 I had what can only be described as the worst headache of my life. The nausea was constant.

Worst. Headache. Of. My. Life.

I rarely get sick, I rarely take pain relievers. I do 3 sets of 50 push ups a day. I’m pretty healthy, and I’ve never been incapacitated. I only say this as background for my next sentence: I was so sick I could not see.

Light hurt me, hurt my head. I could not look at the monitor, or TV. I wanted to be in a quiet, dark room– asleep. With morphine. And the medical student in me solved the mystery: headache, stiff neck, photophobia, no fever. I had finally done what I had been threatening to do for so long: I had popped an aneurysm. I thought: so this is how it ends.

Nausea. Headache. Neck stiffness. Exhaustion.

Exhaustion.

Oh my God, could I be in caffeine withdrawal?

This matches the criteria set by the American Psychiatric Association, which lists the following symptoms after cessation of caffeine use as possible signs of withdrawal [7]:

- Headache

- Marked fatigue or drowsiness.

- Dysphoric mood, depressed mood, or irritability.

- Difficulty concentration.

- Flu-like symptoms (nausea, vomiting, or muscle pain/stiffness)

Dependence seems surprisingly common. In a study done on a random sample of Vermont residents, who consumed at least one caffeinated beverage per week, 11% of users who stopped or cut down on consumption for any reason during the past year met criteria for caffeine withdrawal syndrome [8].

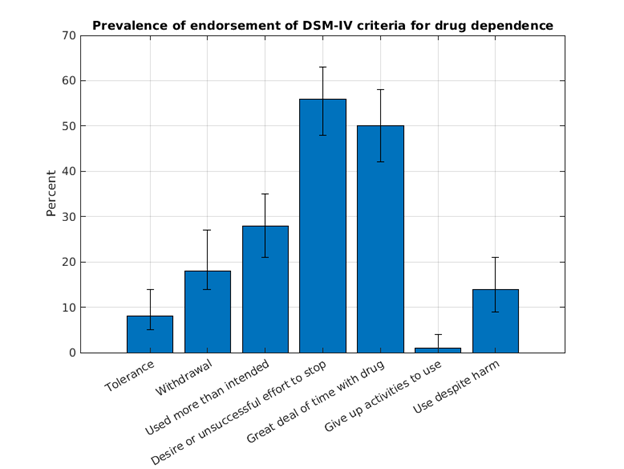

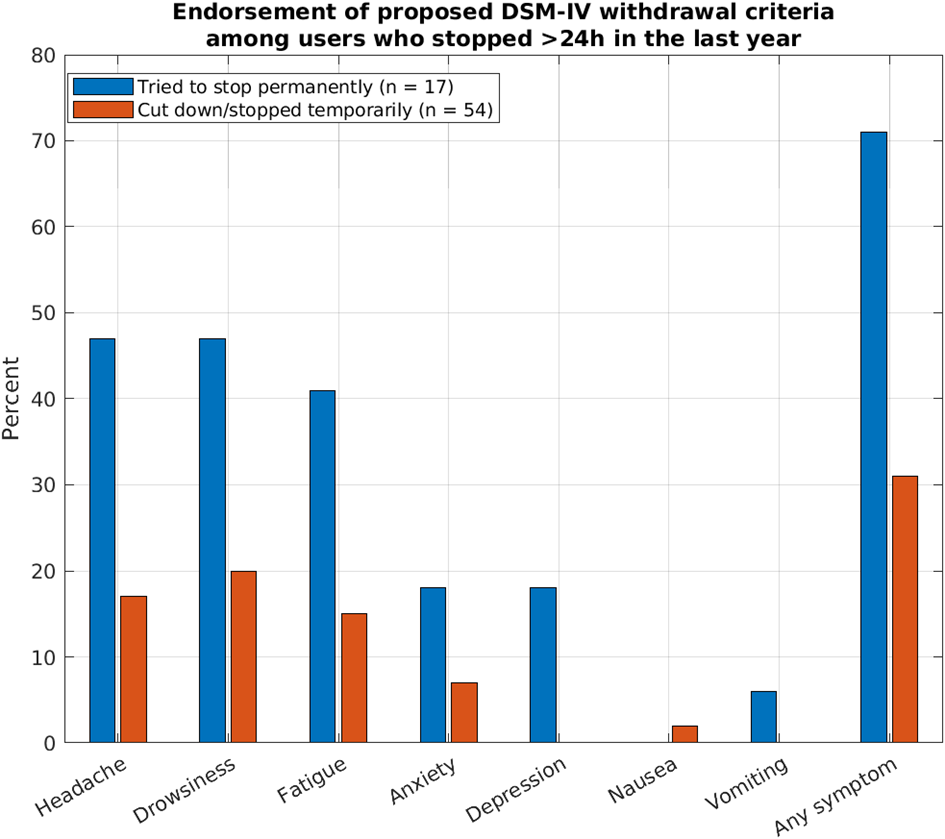

This graph shows the percentage of users who met various DSM-IV criteria with 95% CI. Additionally, 33% said they needed the drug to function (95% CI 26-40). I am especially surprised by how many want to stop usage, this is something I never thought or heard in connection with coffee.

Digging deeper into the data also reveals how participants, who tried to stop or reduce consumption responded.

It seems worrying that 71% of those that tried to stop permanently experienced symptoms of withdrawal, especially, because this study was done on normal users.

This reinforces my conviction to use caffeine only sparingly. I tried to find studies that show withdrawal symptoms by frequency of previous usage, but couldn‘t find any. Examine.com, an online database for supplements, recommends cycling caffeine in order to increase focus, however, they don‘t say how it should be cycled. Therefore, I have to rely on anecdotal evidence from the internet, which is probably among the worst evidence out there. On various forums, it has been suggested that dependence can results if caffeine is only consumed three or four times a week. To keep it safe, I will only drink coffee 1-2 times on days when I feel particularly tired or need motivation.

References

[1] Gladwell, Malcolm (2001, July 30). Java Man. THE NEW YORKER

[2] Diamandis, Peter (2014, August 27). Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/from-beer-to-caffeine_b_5538535

[3] Daly, J., Holmén, J., & Fredholm, B. (1998). [Is caffeine addictive? The most widely used psychoactive substance in the world affects same parts of the brain as cocaine]. Lakartidningen, 95 51-52, 5878-83 .

[4] Nehlig A. (2010). Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD, 20 Suppl 1, S85–S94. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-091315

[5] Haskell, C. F., Kennedy, D. O., Wesnes, K. A., & Scholey, A. B. (2005). Cognitive and mood improvements of caffeine in habitual consumers and habitual non-consumers of caffeine. Psychopharmacology, 179(4), 813–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-004-2104-3

[6] Scholey, A. B., & Kennedy, D. O. (2004). Cognitive and physiological effects of an “energy drink”: an evaluation of the whole drink and of glucose, caffeine and herbal flavouring fractions. Psychopharmacology, 176(3-4), 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-004-1935-2

[7] Meredith, S. E., Juliano, L. M., Hughes, J. R., & Griffiths, R. R. (2013). Caffeine Use Disorder: A Comprehensive Review and Research Agenda. Journal of caffeine research, 3(3), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1089/jcr.2013.0016

[8] Hughes, J. R., Oliveto, A. H., Liguori, A., Carpenter, J., & Howard, T. (1998). Endorsement of DSM-IV dependence criteria among caffeine users. Drug and alcohol dependence, 52(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00083-0