Literature Review - Minimalist Footwear

[Disclaimer: I am not an expert in orthopedics, footwear, statistics, or, in fact, anything. Please don’t rely on this article for advice.]

It is springtime, the sun is out, the temperature is rising. What could be more fun than running around in brightly colored clothes barely being able to breathe while pedestrians are casually watching you suffer? To finally get the beach body the world needs, yesterday I retrieved my running shoes and went outside. Now, my left knee hurts. Apparently, the softeners which make the soles elastic are losing effectiveness over time and after around 7 years I might as well run with bricks tied to my feet.

For some time, I had thought about trying out minimalist footwear. This a fancy term for shoes that try to emulate barefoot running while protecting the feet from abrasions and cuts. Proponents say they protect the wearer from injury, because she is forced to run more carefully and in tune with nature. I have heard good things about them, but most of them anecdotally. So, in this essay, I will take a look at the available literature to determine their influence on injury rates.

I found three prospective studies that investigate this topic. Let’s go through them one after another.

I

Altman and Davis [1] recruited 201 adult runners from online forums who were classified as either shoed runners (SH) or barefoot runners (BF). BFs were required to run at least 50% of their yearly mileage barefoot and the rest in minimalist shoes. Every month for a year the participants reported their mileage and whether they had sustained any injuries. The injuries were classified into plantar surface (PL) and musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries. The first category describes “superficial” damage such as cuts, blisters, bruises and stubbed toes. The second includes for example Plantar fasciitis or ankle sprain. Unsurprisingly, the BF runners sustained many more PL injuries (0.53 vs 0.09 per person). If we take a look at the MSK injuries, the picture looks different.

When grouping all reported MSK injuries (regardless of being medically diagnosed or not), there were no differences between SH and BF groups in the relative number of runners reporting a MSK injury. Interestingly, 48% of BF runners did not sustain any MSK injuries compared to 38% of SH runners; however, this did not reach statistical significance.

[…] However, when normalized for mileage, there was no difference in injury rates between groups.

Taking a look at different MSK injury types, BF runners seem to experience foot injuries slightly more frequently (43% vs 41%) but carry reduce risks everywhere else. For example, 6% of SH runners suffered a back injury vs 0% of BFs. For knee injuries, it’s 35% vs 23%.

As described in the excerpt above, the BF group ran fewer miles on average per week (14.9 vs 25.3). So maybe BF running reduces injury risk by making the wearer run less?

II

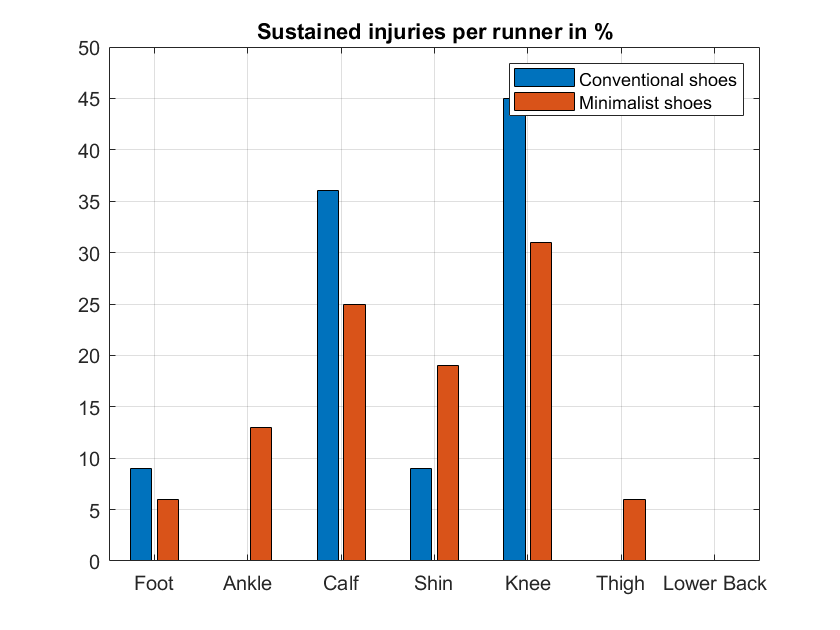

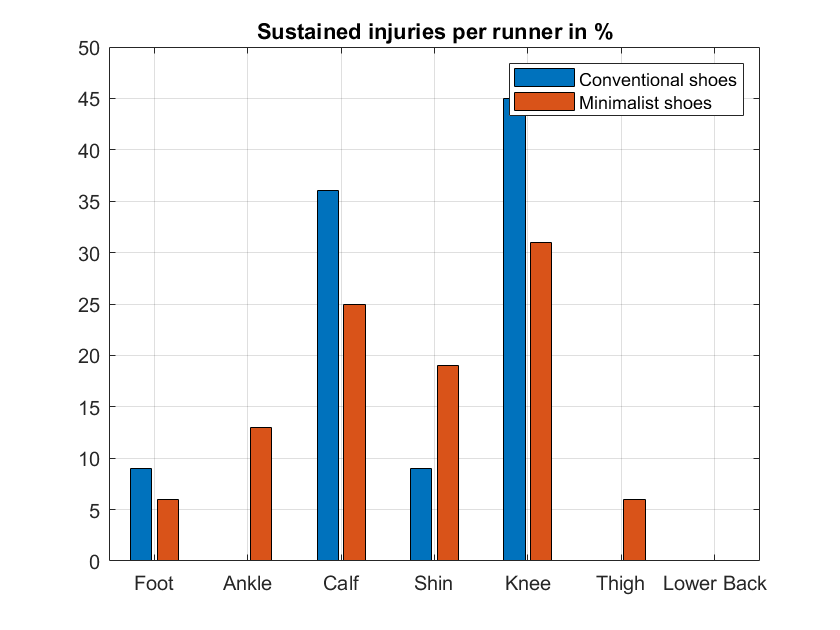

The second good study I found was published in 2017 by Fuller et al. and is called “Body Mass and Weekly Training Distance Influence the Pain and Injuries Experienced by Runners Using Minimalist Shoes: A Randomized Controlled Trial” [2]. A group of 61 trained runners was randomly divided into a minimalist shoes (MM) and conventionally shoes (CS) group. Over 26 weeks they gradually increased the time in their allocated shoes. Subjective pain intensity and injury rates were measured. In the CS group, 37% of runners suffered an injury versus 52% in the MM group. Below, you can see these numbers broken down by injury type. Please keep in mind that the sample sizes are small, so low confidence here.

More CS wearers sustained knee injuries which fits well with the other study, but overall, it’s hard to read anything definite from this data. The numbers seem all over the place and in the case of calf and shin, even counterintuitive.

Additionally, the authors also wanted to assess how much pain the runners in both groups felt. They achieved this by letting the subjects point out the worst running-related pain they had felt in the past week on a 100mm scale (0 mm -> no pain and 100 mm -> worst pain).

As you can see, MS participants fare considerably worse than CS. This is true even for body parts where minimalist shoe wearers reported fewer injuries, such as the knee. I am confused by this result. Maybe MS runners think they are getting hurt more than they are in reality? It is also noteworthy, that the MS group ran less on average than the CS group (20.7 vs 24.2 km per week), maybe because they are in pain more often? This begins to look bad for the barefoot gang.

So, all hope is lost? Can truly nobody benefit from barefoot running? Should I give up on running and get into e-sports?

The authors also took a look at the relationship between injury rates and weight, which led them to an interesting finding.

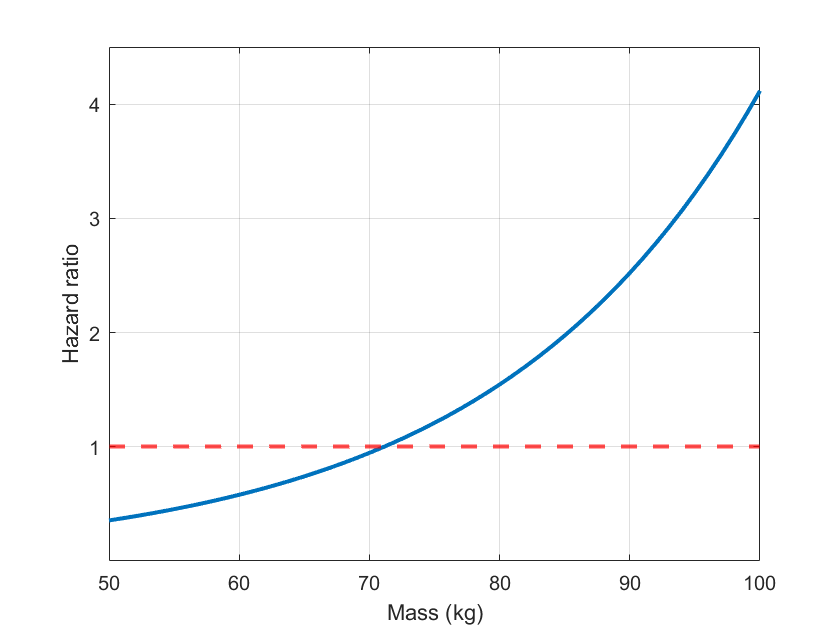

For runners using minimalist shoes, sustaining an injury became increasingly more likely with increasing body mass above 71.4 kg and increasingly less likely with decreasing body mass below 71.4 kg (Figure 5). Runners using minimalist shoes who had a body mass of 85.7 kg experienced a moderate increase in risk of injury (model 2: HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.10-3.66; P = .02). The model estimated that 68% of runners weighing 85.7 kg and using minimalist shoes would sustain an injury after 26 weeks of running compared with 22% of runners weighing 85.7 kg and using conventional shoes (RR 3.09; Figure 6). In contrast, runners using minimalist shoes with a body mass of 57.2 kg did not experience statistically significant reductions in risk of injury (model 2: HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.15-1.66; P = .26).

The study also contains a graph to accompany these claims which I have recreated here without the standard errors.

The blue line represents the ratio of injury risk for minimalist vs conventional shoes. The intersection with the red line marks the point of equal danger. Runners weighing 71.4 kg are equally likely to get injured wearing MS or CS. Runners lighter than that were safer in minimalist shoes, but heavier runners carried more risk from them. Intuitively this makes sense, but the error rates make the result look pretty shaky.

III

I hope you are not confused yet, because it gets even weirder. In the third study, Ryan et al. [3] randomly assigned runners to one of three groups: conventional shoes (CS), partially minimalist shoes (PM) and full minimalist shoes (MM). For 12 weeks they trained and reported their injury rates. Here are the findings:

Overall there were 23 injury events recorded over the 12-week period resulting in an injury rate of 23.2% (see online supplementary table S3). There were more injuries in both minimalist groups than the neutral group contributing to a 160% and 310% RR of injury in the full minimalist and partial minimalist group, respectively. Kaplan-Meier analysis reported a significant difference in the number of injury events over time across footwear condition driven by the disproportionate number of injury events reported by runners in the partial minimalist group (figure 2). Based on injury event data, there is a higher likelihood of experiencing an injury with minimalist footwear, particularly with the partial minimalist condition. Outcomes from the RMANOVA report no significant group effect for FADI scores (figure 3). For the VAS pain scales, comparison of the pain scores over the 12-week period report little difference (see online supplementary table S4). Only in VAS for shin/calf pain did participants wearing full minimalist footwear report significantly (p<0.01) greater pain than both other footwear groups (see online supplementary table S5).

What’s going on here? The partially minimalist group is approximately twice as likely to get injured as the fully minimalist group. How could we explain this?

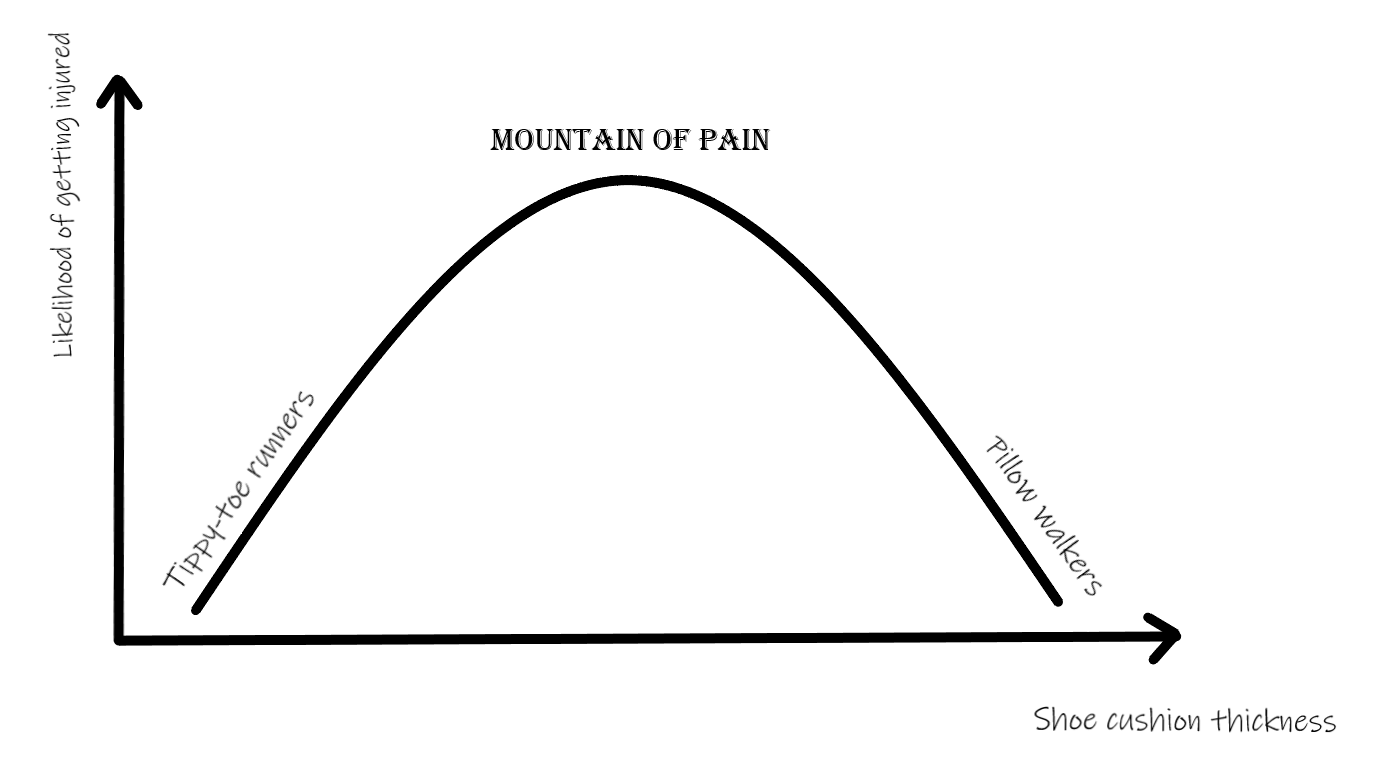

Maybe, the relationship between cushioning and injury risk is best described by a bell curve. Runners with ultra thin soles tread so carefully that they rarely hurt themselves and runners that walk around with 600€ 10cm thick foam shoes are insulated against danger and can stomp as much as they want.

Even though it fits the data, this theory is tongue-in-cheek and I don’t believe in it at all. I expect the body to constantly make an internal calculation on how careful it walks in relation to the terrain and ground solidity. I also expect this relationship to be approximately linear. The “Mountain” theory only makes sense if there is a binary cutoff between careful and careless, a hypothesis, for which I have never seen any indication. This study leaves more questions than answers and I would love to investigate the data more, however, the publisher decided to remove the supplement leaving us in the dry. It Is also noteworthy that the relationship between the fully minimalist and the conventional shoes was not significant. You can find a good discussion on this study, including comments from the main author here.

IV

I have focused on these three papers, two of which were randomized because they are prospective studies, reducing the risk of bias. If we just take a random sample of minimalist shoed and conventionally shoed people and compare their past injuries, this confounds the results, because only people with enough feet might stick to minimalist shoes. However, a rich literature of retrospective research exists. If you want to learn more, I can recommend this article. The author presents a review of the history of minimalist shoe injury studies and is skeptical that they are safer than conventional shoes.

V

Overall, this literature review was very successful for me. Nevertheless, I am disappointed. I had wanted minimalist shoes for quite some time and hoped this essay would give me a reason to go out and get them. In fact, the opposite has happened. I am surprised how badly they were doing compared to conventional shoes. Not one of the three prospective studies showed a reduction in injury rates when adjusting for mileage and I have a suspicion that a mechanism by which minimalist shoes reduce injuries is by making runners run less. Even though the first study hinted at a reduction of knee injuries, the fact that minimalist runners in the second study reported more knee pain leaves me doubtful. The third study (non-significant) outcome that runners weighing less than 71.4 kg are safer with less shoe is interesting but a single paper with unavailable data will not make me switch sides. I will therefore buy some super soft cushioned running shoes.

I am also surprised how high the baseline for running injuries is. Shouldn’t an animal that is a natural long-distance runner be a bit more sturdy? Anyways, stay tuned for the upcoming review of the world’s best artificial knee implants!